Bodies and Time... Gaspar Noé

Inside Gaspar Noé...

In Gaspar Noé's films, time plays a more than essential role...

"The older I get, the more hazy my memory becomes; I don't know if it's because my hard drive is full and retains less data, or if it's simply because my brain isn't working as well. I'm not very concerned about posterity – my father (The painter Luis Felipe Noé) was more so. In any case, as time goes by, I am more at peace with the present than I was at twenty. Also, the older I get, the less I fear death."

"I wonder what form films will take in the future. Their longevity is subject to the future of humanity. It's not like a metal monument; films will remain if they can be read in their current format. But if there's a Third World War, the hard drives that contain them could be irradiated. Films age quickly, don't they? So I make them as I go. I'm happy to live in the present."

"At the age of ten or eleven, accompanied by this friend whose grandfather was a cashier in a movie theater, we would go see two films a day. At ten, I went to see Death Wish (Michael Winner, 1972). Movie theaters were the best thing in life for me. Buenos Aires had between one hundred and two hundred of them. They all closed to become theaters or supermarkets. In Argentina, as everywhere, people consume films via streaming platforms. Perhaps it's as a reaction to this that I don't have a streaming platform at home."

"In Argentina, there isn't a single Blu-ray store left. I like the physical object: it's a collector's thing. 2001: A Space Odyssey" (Stanley Kubrick, 1968), I can't own it. How can you own someone else's work? Through little plastic models or posters. But also Blu-ray. I admire Dreyer's films, like The Day of Judgment (1943) or The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928); I think to myself, "Hey, I have the best edition, with this bonus feature." I once gave a DVD to dancers from Climax, so they could see a film, by me or someone else; they would put it on the shelf without knowing what to do with it, as if it were a floppy disk.

Gaspar Noé

Gaspar Noé films bodies that love each other, lose each other, collide, or are consumed. He transforms cinema into a physical experience, often painful, sometimes ecstatic. Now in his sixties, Gaspar Noé continues to forge a unique path, at the crossroads of sensory nightmare, hallucinatory trip, and meditation on mortality. A portrait of a filmmaker who looks darkness in the face—and elevates it.

vertigo as a language

In Gaspar Noé's work, nothing is left to chance, especially not the feeling of disorientation. From his earliest steps in cinema, he conceived his films as sensory labyrinths, experiences of altered consciousness, where time slips away and points of reference vanish. I Stand Alone (1998), his first feature film, already set the tone: the story of a racist and incestuous butcher filmed with suffocating silences, mental flashbacks, and brutal shifts in tone. It wasn't fiction in the classical sense, but a direct plunge into a sick mind, a desperate cry against modern emptiness.

Then came Irreversible (2002), which would leave an indelible mark on French cinema. The reversed narration, the swirling camera, the unbearable rape filmed in a fixed shot: everything is designed to shock, unsettle, almost make the viewer physically ill. But behind the violence lies a powerful formal intuition: if cinema can hurt, it is because it can also touch reality with a rare intensity.

"I want to make films that leave a lasting impression," he said at the time. Mission accomplished.

A filmmaker of the threshold

From his adolescence, he was fascinated by experimental cinema, underground videos, but also by the classical masters (Kubrick, Bunuel, Pasolini), he dreamed of a total art, which made no concessions to the dominant morality.

This taste for vertigo and transgression culminates with Enter the Void (2009), a hallucinatory journey through Tokyo via the eyes of a murdered young drug dealer. Filmed in subjective vision, influenced by the Tibetan Book of the Dead, this insane project pushes the boundaries of representation: death, reincarnation, intrauterine flashbacks, psychedelic visions… The film is a unique sensory trip.

Gaspar Noé seeks neither consensus nor easy answers. "I make films to live an experience, not to tell stories," he says. An aesthetic of the threshold, between life and death, love and nothingness, the sublime and the abject.

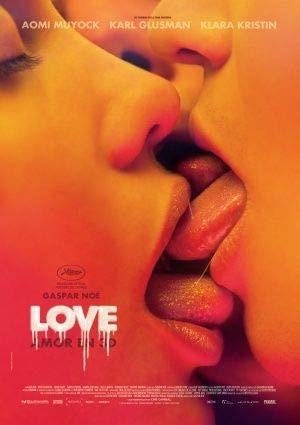

Love, drugs, and then the end

Love (2015), is filmed in 3D. In an era where sex on screen is increasingly sanitized, choreographed, and desexualized in the name of political correctness or collective unease, Love dares to be simple and beautiful in its directness. Not to shock, but to remind us that the body in love is a cinematic territory. That tenderness, desire, and sadness can be expressed there without manipulative music or academic editing. Love is perhaps one of the rare post-2000 films to depict sex without fetishism or moralizing, but with an infinite sadness.

In 2018, Climax Noé confirms that he still manages to surprise: a claustrophobic drama set in a dance school, where a group of young artists descends into madness after unknowingly taking LSD. Strangely political, the film explores the collective, youth, and latent violence. Dance, trance, chaos – Noé's formula reaches an almost hypnotic level of mastery here.

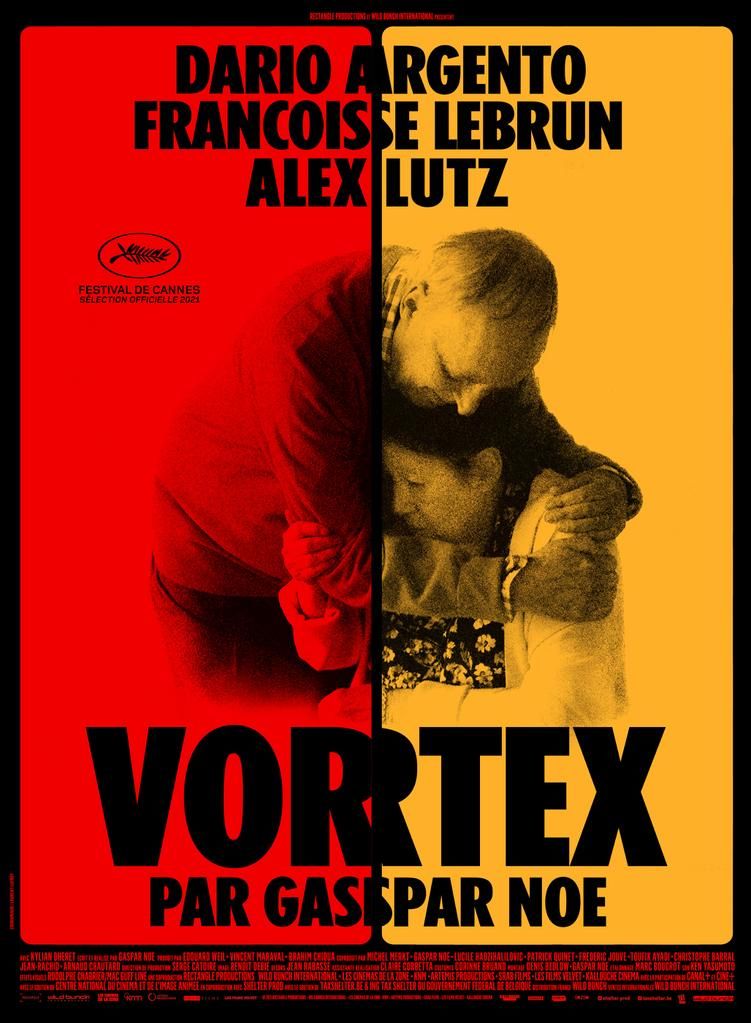

But it's with Vortex (2021) marks a dramatic shift for the filmmaker. Filmed in split screen, this drama about an aging couple grappling with Alzheimer's disease is a world away from his past provocations. Restrained, understated, and profoundly human, Vortex is as moving as it is shocking. No sex, no drugs, no strobe lights—just the inexorable disintegration of memory, love, and life itself. The film is dedicated to all those "whose brains decay before their hearts."

A free craftsman

Gaspar Noé doesn't direct much, but he directs freely. He finances his films independently, chooses his actors from the street, and often works with a small crew. He doesn't belong to any school of thought, doesn't attend formal dinners, and shuns speeches. What he says, he says with his camera. And so what if it's unsettling?

He is one of those rare filmmakers whose universe is instantly recognizable. And who, despite the "provocateur" label, works towards a kind of inverted spirituality, a violent contemplation of reality. A cinema of vertigo, of the threshold, of doubt – but also, of beauty in its rawest form.

Gaspar Noé is not trying to please. He is trying to reveal. And perhaps that is what makes him one of the last true auteurs of our time.

This site is dedicated to the filmmaker Gaspar Noé. We wanted to gather here a large number of interviews, features, and reports about the director. From trailers for his films to music videos, most of the material presented highlights the importance of image and sound in Gaspar Noé's universe. This site is regularly updated to reflect current events. This space is yours, and all contributions to its development are welcome.

We are neither an official site nor able to forward your requests to Gaspar Noé.