I STAND ALONE INTERNATIONAL POSTERS

The poster for I Stand Alone (1998), Gaspar Noé's first feature film, is quite striking and perfectly captures the director's world. This poster has become emblematic of Noé's cinema: an advertisement that is already an act of aggression, that doesn't sell a film as entertainment but as an ordeal.

More than just a promotional tool, the poster acts as a warning. It puts the viewer in the line of fire, forcing them to confront the brutal experience promised by the film. By adopting the graphic codes of exploitation cinema—aggressive typography, shocking imagery—Noé subverts advertising into an act of provocation.

At the time of its release in 1998, this marketing strategy was a radical departure from the polished campaigns of French cinema. It already embodied the filmmaker's approach: breaking conventions, provoking unease, and making each image a confrontation. With this poster, Gaspar Noé doesn't simply sell a film: he threatens, he provokes, he puts his viewer on high alert.

Twenty-five years later, the poster for I Stand Alone remains an icon of radical cinema, a declaration of war as much as a promise: that of a cinema which does not caress, but which strikes.

Red, rage, isolation: the French poster for I Stand Alone

From the outset, the French poster for I Stand Alone adopts an aesthetic that is far more striking than violent. The raw red background is striking, radiating anger and psychological disintegration. In the center, Philippe Nahon, shirtless, stares at the camera with restrained rage, his sculpted face a silent threat against the established order.

The graphic design is uncompromising: stark, aggressive, minimalist typography, a sign of a film that seeks neither stylized beauty nor disembodied aesthetics. On the contrary, it champions the urgent aesthetic of primal urges, of defilement, of the margins of French society. When, in certain versions, his hand grips the map of France, it is an image of a man suffocating under the weight of a corrupted country—the constricted hexagon becomes a symbol of oppression, unease, and revolt.

This poster, far from promising an outrageous spectacle, creates a palpable unease. It exerts visual pressure, like the film itself, and yields nothing to seduction. It is a visual social and psychological treatise, an invitation to confront reality. Twenty-five years later, this image remains the graphic and sensory manifesto of a cinema on high alert, radical, visceral.

The poster for the film I Stand Alone, a sequel to the short film Carne, was designed by graphic designer Denis Esnault. In an interview, he stated that he worked directly with Gaspar Noé on the poster's creation. Together, they reworked the title by playing with the design of the Life Magazine logo and subtly incorporated the word CARNE—it becomes apparent when we see "France" supported by Philippe Nahon's hand, revealing RANCE, an anagram of "CARNE".

When I Stand Alone crossed the Atlantic, the American poster took on a completely different look than the French version. Where France showed Philippe Nahon, a red-faced and furious figure, the American edition chose a more universal language: that of frontal clash and explicit threat.

Here, the composition is darker, sometimes minimalist, with an aggressive use of typography. The rave reviews are often prominently displayed, delivered like sledgehammer blows. American marketing capitalizes less on the film's social dimension than on its potential for scandal. The poster is marketed as an extreme product, a "dangerous movie" aimed at viewers eager for transgression.

This visual strategy accentuates the exploitation film aspect, whereas the French poster, despite its chromatic violence, retained a symbolic and almost political dimension (man crushed by his country). In the United States, the message is simplified: the viewer is not buying a radical social commentary, but a psychological survival experience.

The result: the American poster isolates the film as a cult object, an underground curiosity, rather than a social manifesto. This change illustrates the difference in reception: in France, I Stand Alone was part of a reflection on the unease felt in France at the end of the 1990s; in the United States, it becomes an extreme product of radical cinephilia, a film whose poster almost promises a test of endurance.

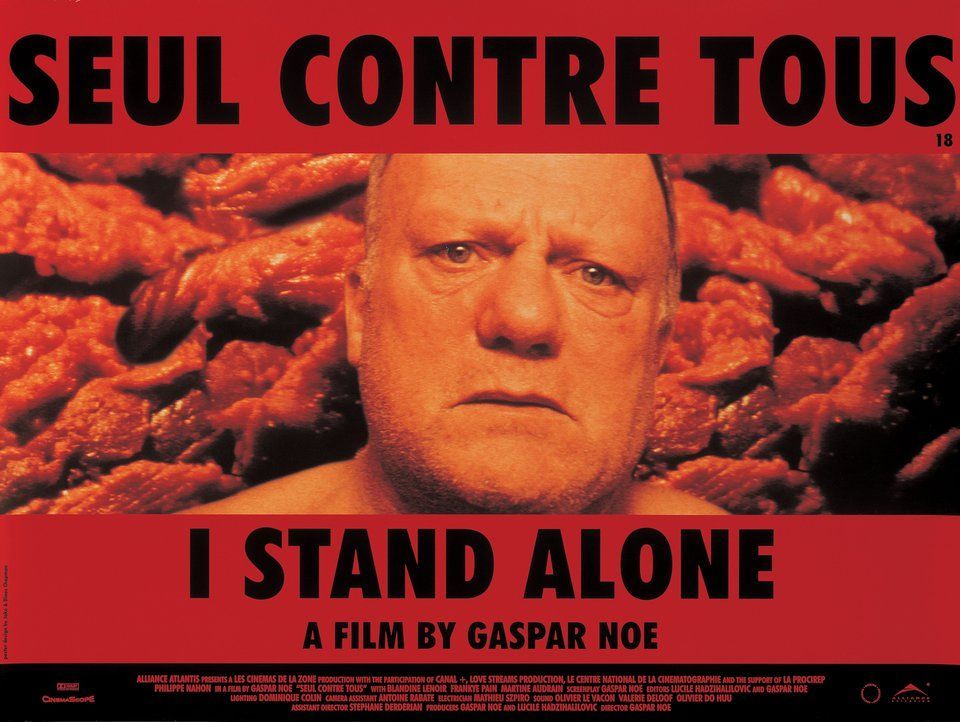

In 1998, when Seul contre tous crossed the Channel to become I Stand Alone, the British poster adopted a radically different aesthetic from its French version. Here, there was no social symbolism or body bathed in a grimy red. The quad format (30 × 40 inches), traditional in English cinemas, accommodated a frontal composition: the butcher's face (Philippe Nahon) dominated the space against a saturated red background that evoked anger, flesh, blood, and urgency.

This poster is not the work of an anonymous marketing studio: it is signed by the Chapman Brothers, figures of British contemporary art known for their taste for provocation. Gaspar Noé himself has said he is fascinated by this creation.

"I love the poster Jake and Dinos Chapman designed for its release. It's much better than the French poster. It reminds me of Eraserhead , the most nightmarish film ever made. The title I Stand Alone was difficult to translate into English. Literally, it means 'alone against everybody.' That sounds awful, which is why we came up with I Stand Alone. I like it. It's very masculine and less paranoid than the French poster. I suggested to the distributors that they write 'in the bowels of France' above or below the title. But perhaps they thought using the word 'France' on the poster would be bad publicity for the film. I don't know… But their choice to use the Chapmans was excellent. I love their work. It reminds me of the fear under the influence of hard drugs." The Guardian 1999."

The title, translated as "I Stand Alone," sounds different from the original French. Where "Seul contre tous" (Alone Against All) evokes paranoid isolation, the English version emphasizes the virile and martial stance of a man standing against the world. It's a stark declaration, a survival slogan that perfectly captures the nihilistic spirit of the film.

In England, this poster established the film as an underground cult object, at the crossroads of extreme cinema and contemporary art. More than just an advertisement, it stands as an independent graphic work, an aesthetic intimidation that prepares the viewer for the shock. The British Quad doesn't simply illustrate a film: it puts the audience in a state of war from the outset.